With a rumored 2015 limited rerelease of Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair as a single film, Quentin Tarantino’s two-part revenge epic is entering the Hollywood conversation once again. The postmodern auteur announced his plans at the 2014 Comic Con International in San Diego, where he also confirmed his forthcoming project, The Hateful Eight. The Whole Bloody Affair will be the full four-hour cut of Kill Bill that Tarantino first screened at Cannes Film Festival in 2003 before Miramax Films distributed it in two parts, complete with O-Ren Ishii’s (Lucy Liu) anime backstory extended by thirty minutes of deleted footage.

Tarantino became one of my favorite directors, second only to Sir Alfred Hitchcock, because of Kill Bill. I was home from my freshman year of college on spring break, and my grandmother and I watched all his movies because that’s how impressed she was with Django Unchained (2012) when she saw it in theaters and we’d never seen anything else he’d ever done before. We started Volume I (2003) at nine or ten o’clock at night and planned on finishing Volume II (2004) the next day, but we stayed up until two in the morning finishing Volume II, and we stayed up until three talking about what we’d just witnessed.

For me, Kill Bill is one of those films that you never forget the experience of seeing it for the first time. It was unlike anything else I’d ever seen, before then or since. I spent all of Volume I worrying that my grandma hated it, but she’s even more obsessed with it than I am.

Even my grandma loves Kill Bill.

Except for a Golden Globe nomination for Uma Thurman (The Bride, Black Mamba, Beatrix Kiddo) in parts one and two and one for David Carradine (Bill, Snake Charmer) in Volume II, Kill Bill received no recognition from any major awards shows. Pulp Fiction (1994) is considered the most influential film of the nineties and Django Unchained is, arguably, Tarantino’s most accessible picture, but Kill Bill is seldom regarded with such esteem. I submit that Kill Bill is the greatest addition to Quentin Tarantino’s filmography, not just because it’s one of my all-time favorite movies, but also because it’s his most “Tarantinoesque” feature.

Magnum Opus

Daryl Hannah (Elle Driver, California Mountain Snake) has gone on the record as saying that Kill Bill is Tarantino’s self-anointed “magnum opus.” Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) and Apocalypse Now (1979) are significant because The Godfather Trilogy was so successful that Paramount Studios entrusted him with a blank check to pursue his artistic vision to its fullest extent. Since The Conversation and Apocalypse Now yielded a relatively lukewarm response when compared to The Godfather, it is noteworthy that notoriously skittish contemporary producers granted Tarantino “carte blanche” the way Bob and Harvey Weinstein did for Kill Bill.

And like Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, The Godfather is popularly regarded as one of the best American films ever made, but I’d argue that The Conversation surpasses The Godfather. Although it’s not as “big” as The Godfather, The Conversation is the most innovative thing to happen to cinematic sound since Alan Crosland’s The Jazz Singer (1927) first popularized it, with Harry Caul (Gene Hackman) obsessively reconstructing a glitchy recording of a conversation between a cheating wife (Cindy Williams) and her lover (Frederic Forrest) that the cuckolded husband (Robert Duvall) hires Harry to surveil. The emphasis on one word in one sentence makes all the difference in the meaning and the outcome of the conversation, and, even though the plot is seemingly uneventful, it’s the only suspense film I’ve ever seen where I had to remind myself that it was just a movie because I was so freaked out.

Running at three hours per installment, The Godfather Trilogy is far less nuanced, and much less personal to Coppola than The Conversation is. Martin Scorsese’s GoodFellas (1990) is a superior gangster flick, and HBO’s The Sopranos (1999-2007) is more literary and watchable than The Godfather. Anybody can make something as good as or better than The Godfather with the same raw materials, but only Coppola could make The Conversation as great as it is.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

The same goes for Kill Bill. I’m not a martial arts or kung fu fan, by any means, and I’m not the action and adventure aficionado I used to be when I was younger, but I still love Kill Bill, more than most other movies. Tarantino cultivated his obsessions with Hong Kong imports on the Los Angeles grindhouse circuit as well as Spaghetti Westerns in the video store where he worked – mainstream tastes, his are not – and he set them all in modern-day California, Japan, Texas, and Mexico, in a jarring technique which generates a stylistic conflict as larger-than-life and over-the-top as the clash between The Bride and the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad.

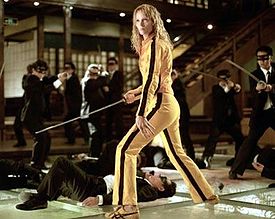

The genre crossovers trigger a visceral response in the audience as powerful as The Bride’s quest for vengeance, even if you aren’t personally invested in the borderline surrealistic world she inhabits. Her penchant for breaking the fourth wall, like she does in her opening monologue to the camera in Volume II, violates the barrier between spectator and spectacle and elevates the film’s mythology to a self-referential, transcendent level, where it openly acknowledges its more absurdist elements and invites the viewer to revel in them. It’s as global as East meets West, Bruce Lee versus Sergio Leone, a blonde Uma Thurman in a samurai swordfight with an entire yakuza gang, and it’s a paradox only Quentin Tarantino could pull off, a Hollywood asset who got his start with the entrepreneurial Reservoir Dogs (1992), which Empire named “the greatest independent film ever made” (even though it’s my least favorite Tarantino).

Not even Brian De Palma, another advocate for genre films, could make Kill Bill as well as Tarantino did. Tarantino named De Palma’s Stephen King adaptation, Carrie (1976), on his list of “the twelve greatest films of all time,” and De Palma made a name for himself in the realm of “borrowing” from other filmmakers throughout his career, especially Hitchcock, with Obsession (1976) echoing Vertigo (1958), Dressed to Kill (1980) mirroring Psycho (1960), and Body Double (1984) paralleling Rear Window (1954). Carrie, Dressed to Kill, and Blow Out (1981, inspired by Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) and The Conversation) are fine films – Carrie and Dressed to Kill are a couple of my all-time favorites – but Obsession and Body Double highlight De Palma’s filmmaking weaknesses in that they try too hard to be like Hitchcock’s masterwork, Vertigo.

The voyeuristic Body Double is, on the surface, more like Rear Window, but its themes of shifting identities and its neurotic protagonist (Craig Wasson suffers from claustrophobia whereas Jimmy Stewart suffers from acrophobia) are drawn from Vertigo. Obsession is more obvious in its reworking of the same source material, but the results are the same as Body Double: mediocre filmmaking. Vertigo is slow and far-fetched, but Hitchcock makes it work because it’s personal to his own obsessions and disposition; he was born to make it, and genius is the alchemic ability to make something out of nothing.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Kill Bill shouldn’t be as good as it is, but it just is. It’s better than those low-budget exploitation flicks it borrows from (and it does borrow from other movies, with its Ennio Morricone score taken from the likes of Sergio Corbucci’s Navajo Joe (1966)), because, according to Andy Warhol’s “Pop Art” movement of the past half-century, the act of making art out of media relics turns those artifacts into art. We live in a media-saturated world, and pop culture is as much a part of our lives as the basic human needs to sleep and eat; therein lies Quentin Tarantino’s genius, but, rather than attempt to recreate the inimitable (like De Palma failed to do with Vertigo), Tarantino took the basic components of Kill Bill, rearranged them like a DJ remixes somebody else’s music, and he made Kill Bill his own.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Music

Music has always been integral to Tarantino’s work, from the dialogue about Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” at the beginning of Reservoir Dogs to the hit that Dick Dale’s surf rock interpretation of “Misirlou” came to be on the soundtrack for Pulp Fiction. This love of music is more cinematic than anything in Kill Bill, which uses Morricone film scores liberally. Alas, Tarantino is a filmmaker, not a musician, and so his interactions with film scores are more important to a discussion of his art.

Moreover, Quentin Tarantino is a cinephile à la the post-World War II French New Wave. André Bazin’s Cahiers du cinéma introduced “auteur theory” as a critical analysis of directors who, at the time, were largely considered populist showmen rather than serious artists, and, since many of Europe’s finest filmmakers (like Hitchcock) fled to the United State during the war, this was a predominately “Hollywood” discourse (also, France didn’t have much of a film industry during Nazi Germany’s occupation). Jean-Luc Godard (no relation), a mentee of Bazin’s, made Breathless in 1960, with a Humphrey Bogart-worshipping main character.

A fascinating crosstalk subsequently took place between Hollywood and France, with the Golden Age of Old Hollywood influencing the “Nouvelle Vague” and France influencing the “New Hollywood” of Francis Ford Coppola and Brian De Palma. Tarantino is the product of “New Hollywood” and all its international origins, and Kill Bill is not so much one film as it is many films, a Westernized (both culturally and generically) take on Toshiya Fujita’s Lady Snowblood (1973). The choice to split it into two parts underscores this multiplicity (even though that choice was made to appease the moviegoing public with more traditional runtimes).

Truly, Kill Bill has something for everybody (if not everything for everybody).

Popular Culture

Quentin Tarantino takes Kill Bill to another level of self-reference with its relationship to Pulp Fiction. In a star-making performance, Uma Thurman played Mia Wallace in Pulp Fiction, a gangster’s wife who starred in the failed pilot for a television show (Fox Force Five) with a cast of characters that sounds more than a little similar to the Deadly Vipers in Kill Bill (particularly Mia’s character, “the deadliest woman in the world,” a prototype for Thurman’s Bride). Thurman and Tarantino, in an informal creative partnership known as “Q&U,” came up with the idea for The Bride while they were still working together on Pulp Fiction.

Tarantino towers so high in pop culture that he’s now able to reference himself. Self-reference is the stuff mythology is made of, only geniuses are capable of mythology, and Kill Bill is more rooted in Tarantino’s mythology than anything else he’s ever done. Using Hollywood money to turn an idea within an idea into a big-budget, two-part extravaganza is a power that few other directors have.

Like Coppola, for example.

Uma Thurman

Uma Thurman is to Quentin Tarantino what Princess Grace Kelly was to Alfred Hitchcock. Acknowledged as his muse, she went from a supporting role in Pulp Fiction to the leading lady in Kill Bill. Tarantino said, “If Mrs. Thurman never met Mr. Thurman, there wouldn’t be a Kill Bill.”

The film is as much about Thurman as it is about her character, as it is about her working relationship with Quentin Tarantino. Brian De Palma had that with Nancy Allen (Carrie, Dressed to Kill, Blow Out) and Coppola had that with Robert Duvall (The Godfather Trilogy, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now). Once more, Kill Bill is an exclusively Tarantino film, the most “Tarantinoesque” film there is.

Sure, Inglorious Basterds (2009) has the highest death toll out of all of Tarantino’s movies (three hundred ninety-six), and who could forget the katana-wielding Bruce Willis in Pulp Fiction? Notwithstanding, Tarantino’s most memorable violence is on display in Kill Bill, and that’s pretty remarkable, considering that Tarantino is memorable for his violence. The Bride doesn’t even have to kill everyone she’s up against, like when she rips out Elle Driver’s eye and leaves her for dead in Volume II.

Beatrix Kiddo is so unstoppable that a new species of parasitic wasp was named after her by scientists in 2013, the Cystomastacoides kiddo. Empire ranked her among their “hundred greatest movie characters” list. Maud Lavin, a cultural historian, claims that The Bride is a site of self-identification for viewers (female viewers in particular) as they confront their own aggression and revenge fantasies.

What I like most about The Bride is that she’s still “feminized” despite the fact that she kicks major ass. She styles her hair long, but she’s still a force to be reckoned with. Artists like Katy Perry and her “Part of Me” music video have noble intentions, but making a strong female character look more “masculine” by cutting all her hair off, for example, sends the wrong message, which is that women have to be more like men in order to be “tough.”

Directorial Flourishes

Kill Bill is full of ‘em. From Beatrix Kiddo having her name bleeped out for the first half to the random cutaway of Uma Thurman in an elementary school classroom raising her hand when the teacher calls Beatrix’s name (after Elle says the name, uncensored for the first time, over the phone to Bill), Kill Bill is quirky Tarantino fare. Michael Madsen cuts a guy’s ear off to the beat of Stealers Wheel’s cheery “Stuck in the Middle with You” in Reservoir Dogs, Uma Thurman tells John Travolta not to be a “square” in Pulp Fiction and a superimposed square appears when she traces one in the air with her fingertips, and O-Ren Ishii’s backstory is told in anime in Kill Bill.

Tarantino connects the different films, too. Madsen’s “Mister Blonde” in Reservoir Dogs is the brother of Travolta’s Vincent Vega in Pulp Fiction, and Doctor King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) mentions a dead wife in Django Unchained, who may or may not be Paula Schultz, the dead woman in Volume II whose grave Madsen (Bill’s brother, Budd) buries The Bride alive in. Kill Bill transports us to a different world, an exciting world, a world we recognize as our own, and it was all but destined to age into a cult classic.

Writing

Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for Pulp Fiction, but Kill Bill earned the director much less credit for his screenwriting here. Granted, it’s not a film that you find yourself quoting as you walk away from it. But, like David Carradine outlines in Bill’s Superman speech in Volume II, Superman isn’t the best-drawn comic book ever, but that doesn’t stop it from being the best comic book ever.

Kill Bill isn’t the best-written Tarantino ever, but it’s still, in my eyes, the best Tarantino ever. Again, it’s the mythology that sets it apart. In a generation or two, if and when McDonald’s goes out of business, people won’t get Travolta and Samuel L. Jackson’s “Royale With Cheese” reference anymore, but we’ll always understand Kill Bill.

I Could Write Volumes About Kill Bill

Get it?

But I’ll stop here before we get lost in it completely. Kill Bill is a pure celebration of what makes movies so enjoyable, from a man who worships movies. Its music and images provoke a reaction in us, even without us realizing why.

It’s a movie that demands to be watched because it makes so little sense that it’s difficult to summarize, but, suffice to say, it doesn’t have to make any sense. We’re the ones who have to make sense of it, and, whenever someone screws you over, no matter who they are or what it is that they did, The Bride will be there in your mind to shut them up with a five-point palm exploding heart technique. Don’t worry, it’s okay to think about.

After all, it’s only just a movie.

I loved this write up! I’m in total agreement that Kill Bill is Tarantino’s masterpiece – though to be honest, it’s a near tie with Death Proof (yes, seriously!).

After the 90s his films became even more personal and experimental, and Kill Bill is definitely his most personal movie, which is part of what makes it so special. It has the spectacle, the humor, the energy, the depth, the emotion, and some of his best characters.

The structure is even more complex and meaningful (in a way) than in Pulp Fiction, it’s more challenging but never feels forced.

Kill Bill is at once his most important and least important film of his career. Completely rich and yet curiously empty (and I don’t mean that as a criticism at all, rather how the film is perceived and how his own name alone is problematic for himself just as much as it liberates him).

It’s easily his most self-aware/self ironic movie and the real turning point as his career moves into the wasteland of the meaningless, culturally vacuous 00’s. It makes Kill Bill feel even more like a tragedy.

I could literally talk about Kill Bill and his other movies for days on end, so if you want to discuss this let me know!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha thanks for your comment! 🙂 I love talking “Kill Bill,” but I can never seem to find anyone else who loves it as much as I do. I think “Pulp Fiction” is too safe and too easy to pick as Tarantino’s masterpiece. And I still haven’t seen “Death Proof” yet, so, sounds like I need to check it out!

LikeLike

Are you on Facebook? Maybe we can talk more on there if you want.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes sir! I have a page on this blog with all my social media links 🙂

LikeLike

I recently rewatched Kill Bill after many years and have to say that Kill Bill is to Tarantino what Goodfellas is to Scorsese.

It’s his best work. A director at the peak of his game and in total control of his craft. Everything in Kill Bill is both great and screams Tarantino. From the dialogue, to the editing, to the music. It just all works and it works so well.

LikeLike

I’ve never seen another film like it, and I can remember one of my professors telling us Quentin Tarantino wasn’t an auteur because another director could emulate his aesthetic and his mise-en-scene, but she must have forgotten about Kill Bill. For being as stylistic and experimental as it is, I don’t think I’ve met one person who didn’t like it. Tarantino’s genius lies in his alchemic, arthouse approach to… well… pulp fiction.

LikeLike

You nailed it young man. The wooden water pump scene w The bride and O ren fighting is both technically and artistically brilliant. He was at the height of his craft. When I watch ” Pulp Fiction ” now, I see a young director still finding his technical craft. I think splitting Kill Bill in 2 has hurt its critical recognition immensely. I even have a framed ” Kill Bill ” poster hanging on the wall of my family room.

LikeLike